Chain of Fools

In an off-brand Little Free Library box on a tiny island in Puget Sound, I once found a pitted and torn copy of a novel I’d never heard of: Diallelon, by Bryn Turnage. The cover was sun-bleached and crusted with salt, like someone had read it at sea. This was a couple years ago, and I’ve been carrying the book with me ever since while I try to think of a way to adequately summarize it and decide whether it’s a work of genius or a failed experiment. Because it’s definitely one or the other. There’s no room for it in the middle of the critical spectrum. Or, I don’t know, maybe my brain’s capacity for nuance has been sanded off by overexposure to the current iteration of the internet.

I have my copy in front of me now, and I’ve never spotted another. The copyright page does not list a date of publication, but my best guess from internal narrative clues is that it was published twenty or so years ago. There’s no trace of the author online.

Naturally, the book has an epigraph: the third verse from Aretha Franklin’s “Chain of Fools”:

One of these mornings

The chain is gonna break

But up until the day

I’m gonna take all I can take

The copyright page lists a small independent publisher in Washington state—Horrible Beast Books—but there is also a note explaining that this is a print version collecting what was originally a self-published web serial. No web address is listed, and my searches through the internet have proven fruitless. This note may be an elaborate prank, or maybe the web serial had so little traffic that it doesn’t appear online or even on archived versions of the net… but if it had so few readers, then why would a publisher, even a small one, agree to produce a print version?

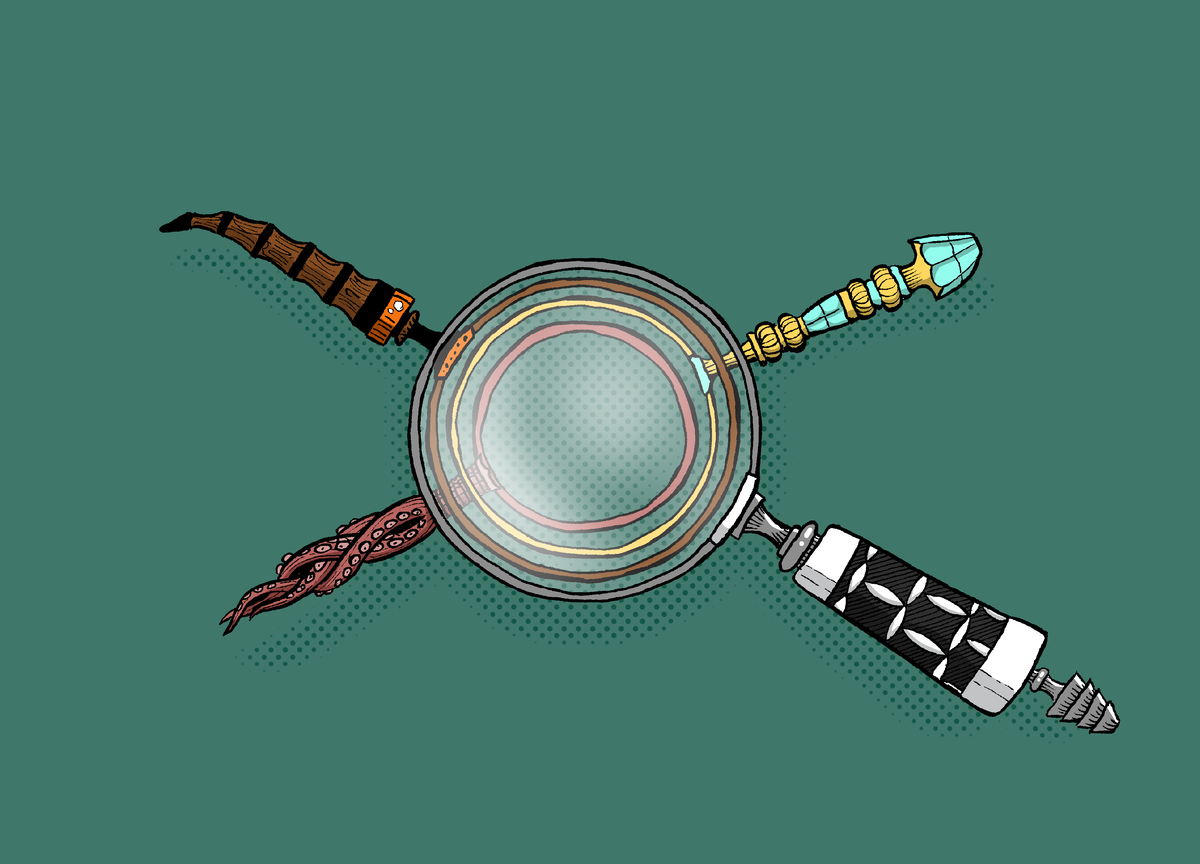

Diallelon is essentially a nested detective novel. There are four narrators—A, B, C, and D—each of whom, starting with B, is following or investigating the previous narrator. Structurally, we move from A to D in order, then back to A, then back to D, then back to A again. Visually, the movement between narrators looks like this:

The novel thus both begins and ends with A as the narrator. A has three sections, B and C each have four, and D has only two. Each new narrator interrupts the previous narrator’s story, sometimes mid-sentence, initially at the moment when the previous narrator first notices that someone is following them.

The novel’s wildly unmarketable title is a strained philosophical allusion: Diallelon is a Greek word, or technically two words, literally translated as “through one another” or “by means of themselves.” The word refers to an idea in epistemology known as the “regress argument” or the “infinite regress problem,” which says that (1) any proposition requires justification, but (2) the justification itself also requires support, and therefore (3) there is an infinite chain or ladder of reasoning and nothing can be definitely proven to be true. Not terribly surprising that this book wasn’t popular in its day—the title itself is a fucking homework assignment.

Luckily, the story itself is slightly more engaging. The setting is a world subtly but unmistakably off-kilter from our own. It’s set in a smallish (fictional) city called Useless Bay, on Whidbey Island, where the mayor and city council abolished the police department four years before the events of the novel. In place of the police, and using its former budget, the city has created several smaller, non-armed departments, such as the Mental Health Response Unit and the Crime Prevention and Food Security Unit. Violent and minor crime rates are at an all-time low, and the nation is watching with eyebrows raised as Useless Bay’s pilot program proves successful year after year. There is talk of implementing its no-cop policies in other larger American cities, but of course there are endless political arguments across the country: It won’t scale, the crime rate must be underreported, etc.

The plot is as follows: A famous private investigator named X has recently begun to enjoy a popularity rare in his profession—glowing magazine profiles, talk-show circuit, multiple true-crime podcasts unraveling his storied and very public cases. He is a modern-day version of the much older gentleman detective trope (I mean “modern” by the standards of the novel, which seems a decade or two out of date). He sports a vape rather than the Holmesian pipe, plays complicated electric guitar etudes in his free time rather than classical violin pieces. He is oldish but in a youthfully craggy salt-and-pepper sort of way. He lives in the posh district of Useless Bay, in a palatial many-terraced villa on the sea. He is rich and white and politically centrist.

Our first narrator, A, is a struggling single father working as a freelance fact-checker for a local magazine. His editor assigns him to fact-check and copy-edit a glowing profile on X; it is the first anniversary of X’s successful solving of a case referred to throughout the novel as “the Dissolution Day Massacre” or simply “the Massacre,” the first major tragedy in Useless Bay since the dismantling of the police. One year ago, all five field members of the Investigative Unit neglected to show up for work on Dissolution Day, the anniversary of the mayor’s official dismantling of the Useless Bay Police Department. The only unit members who did clock in were the two office administrators; they attempted to contact the missing field teams, to no avail. As the hours ticked by, nobody knew what to do or whom to contact, since the unit itself would normally investigate such matters. The administrators suspected a prank. By evening, they decided to check the squad members’ homes, but nobody answered the door at any of their various houses and apartments. Phones and emails went unanswered. The administrators alerted the Crisis Response Unit and clocked out for the day.

The next morning, the administrators were informed that the Crisis Response folks had discovered eight bodies the previous night, all at home, in bed, sheets soaked in blood. All five field members of the Investigative Unit had been murdered, plus the three partners/spouses of those team members who lived with partners/spouses. These team members did not carry weapons, but they were highly trained in hand-to-hand self-defense. No gunshot wounds were found on any of the bodies—the vicious work was all done with knives, seemingly while the victims slept. Critics of Useless Bay’s pilot program immediately flooded the internet with the expected “aha, I told you it was too good to be true” comments. They called for the immediate reinstatement of the police force, for the safety of its citizens.

They were echoed, though far more soberly, by the members of a local fraternal lodge formed by the former cops of the Useless Bay Police Department. “This isn’t about saying ‘gotcha’ or pointing fingers at who’s at fault,” said a spokesman for the Fraternal Order of Displaced Policemen in a prepared statement. “It’s about protecting our friends and loved ones in the city we love best. We laid down our guns when called upon by the mayor, and we are ready to take them up again.”

With the loss of its entire Investigative Unit, the city hired X, now one of the most celebrated detectives in the country but relatively obscure at the time, who immediately agreed to take the case. Within a month, the Island County Sheriff (who had muscled in on the case with the governor’s blessing) had several suspects in custody, at X’s direction. Through a series of elaborate and fiendishly esoteric clues, X determined that the killers were an underground “gang” of five expert housebreakers, the now infamous Filthy Five, who had been quietly robbing people in the area for several months or longer. Allegedly, this gang discovered some secret files in the home of a city council member during the course of one of their robberies; one of the gang members worked as an assistant to this city council member, who was one of the most vocal supporters of the mayor’s police abolition plan. These files showed that the Investigative Unit was aware of the gang’s identities and was closing in on them (covertly, of course, since the squad members didn’t want to endanger the so-far-successful no-cop experiment). So the gang destroyed the files and then killed all the squad members in a single night (the early morning hours of Dissolution Day), each housebreaker breaking into one squad member’s house and killing sleeping partners too when necessary, according to X. (The far-fetched nature of this plan is intentionally meant to engender skepticism in the reader, I think.)

X was celebrated, the case made national headlines, and the “gang” members were taken into federal custody. X himself declared his reluctant support for the reestablishment of the police department, citing the need for “law and order” in a joint press conference held in tandem with the Fraternal Order of Displaced Policemen. The mayor pushed back in her own press conference later that same day, claiming that the existence of a police department wouldn’t have prevented the murders. She pointed out that the non-armed Crisis Response Team had prevented or stopped dozens of violent acts over the last few years.

Now, a year later, the city is starting to fracture—the mayor’s approval rate is slowly but steadily shrinking, though so far she’s still clinging to a bare majority. Even the President of the United States himself has caught wind and weighed in, calling Useless Bay “a lawless hellhole” run by a “ditzy, nasty woman of a mayor.” He once threatened to call in the National Guard to police Useless Bay, which he characterized as a sort of anarchist fortress with hourly violent riots, but then he got distracted, first by preparations for a military parade he decided to throw himself for his birthday, and later by vehemently denying he’d been close friends with a notorious pedophile who’d died in prison. He had a lot on his plate.

Back in the present, our narrator A pulls an exhausted all-nighter to fact-check the article about X and the anniversary of him solving the Massacre. He comes across a few questionable facts and contacts X’s assistant the next morning. He is surprised when X himself immediately calls him back and asks A to stop by his office for an in-person meeting, saying he prefers face-to-face contact—he’s old-school like that. So A has to quickly arrange for last-minute childcare for his two-year-old son (his sister and her wife agree to watch the boy, in exchange for A watching their twins the following weekend), and he takes the train across town.

At X’s office, A exchanges strained small talk with X’s assistant for an hour before finally being ushered into the inner office. No drinks are offered. The room is windowless and unfurnished; the walls are covered with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves filled to bursting with famous works of criminology, psychology, and art history, but there is nothing on the room’s hardwood floor—no chairs, desk, or couch, not even a rug. He stands there uncomfortably for a while until X rushes in between appointments, apologizing profusely. X explains that the bizarre lack of furniture is a psychological trick that enables him to concentrate more fully—something about the body’s discomfort hastening the mental process of deduction. So X and A stand awkwardly in the center of the room as they have their brief conversation. X allows A to audio-record the conversation on his phone.

X promptly clears up A’s handful of fact-checking questions: Yes, he was born in 1962, not 1964 as the profile claimed. Yes, the tenth word of that long quote should be “apposite,” not “opposite.” No, he did not fail out of a European police academy as a young man—he never attended at all—that’s a vile rumor circulated by his enemies. Yes, he does indeed have a photographic memory, of sorts, though he prefers the more exact term eidetic. No, the deciding clue in the Massacre case was not a specific brand of rollerball pen but rather a felt-tipped one. Yes, the lack of biographical information about him online is intentional; he prefers to keep the details of his career prior to about four years ago, when he first came to national attention, shrouded in mystery, as he was undercover for much of that previous time. Prior to that, he was a well-respected investigator in certain circles but was intentionally hard to reach, with no online footprint—word of mouth only. You had to know someone who knew someone, and with certain discreet inquiries, if you were lucky, someone might hand you a thick and heavily embossed black card with only X’s name and a phone number in gold ink.

Throughout the conversation, X has been standing stock-still with his hands in front of him. The only movement he makes while talking is a light drumming with one finger on a vivid crimson bracelet or wristband, which A assumes is a fitness tracker or smartwatch.

A thanks X for his time, stops the recording, and leaves. He collects his toddler from his sister and has a nice day at the boardwalk with him. Later, when the boy is asleep, A listens to the recording and uses it to correct the article, which he then sends off to his editor. But something bothers him about the recording, so he listens to it again and again. After dozens of repeats, he finally notices that he can just barely make out the tapping of X’s fingernail against his fitness tracker. And it doesn’t sound like casual drumming anymore; there are patterns, intentionality.

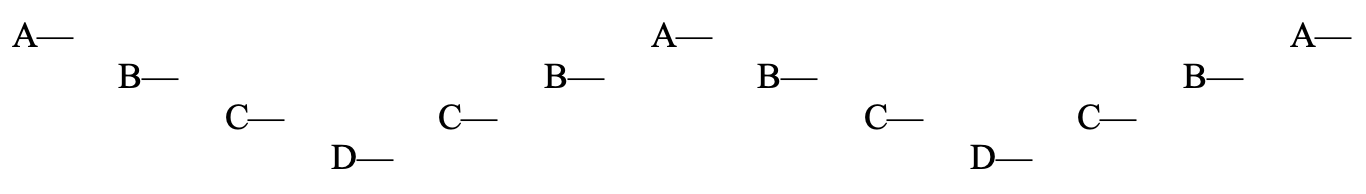

Bewildered, A looks up Morse code and spends the next several nights laboriously attempting to translate X’s taps. But all he comes up with is gibberish, since simple tapping isn’t really ideal for distinguishing between the short and long beeps necessary for Morse code. He gives up for a while, thinking the regularity he heard must have been music or drumming after all. But then, weeks later, while fact-checking a different article, he stumbles across a wiki entry on something called the “tap code” or “knock code,” which prisoners use to communicate by tapping on the walls or bars of their cells. The code is much simpler to memorize than Morse: You take a 5-by-5 Polybius square and assign each letter of the Latin alphabet to each square, starting in the upper-left cell (and combining C and K into a single square to account for all 26 letters in a 25-cell grid). The first row is A, B, C/K, D, E; the second row is F, G, H, I, J; and so on.

|

A |

B |

C/K |

D |

E |

|

F |

G |

H |

I |

J |

|

L |

M |

N |

O |

P |

|

Q |

R |

S |

T |

U |

|

V |

W |

X |

Y |

Z |

Each letter is represented by two sets of taps: The first number designates the row (e.g., one tap for the first row of the square, comprising A, B, C/K, D, E) and, after a quick pause, the second number designates the column within that row (e.g., four taps for D). Then a longer pause is used between letters. It takes an enormous amount of time to tap out words and sentences, but it’s an efficient and relatively simple code.

Excited by his discovery, A again spends several nights translating X’s taps from the recording. After hours of trial and error, he is thrilled to discover he’s right: X encoded a message in his tapping, which means he was having two distinct conversations simultaneously—an almost superhuman feat. And since X is a musician on the side, his taps are rhythmic enough to make it relatively simple to transcribe. He keeps a fairly steady tempo: one beat of rest between row/column numbers, two beats of rest between individual letters.

A doesn’t know who the message is for. Probably someone connected to the watch (or phone?). The message is as follows, the lack of punctuation stemming from the limitations of the tap code:

false alarm thought he might be detective posing as factchecker but no just a regular dullwitted jackass so no danger proceed with dead drops as planned

Furious as this dismissal, and having for some time harbored secret dreams of becoming a detective himself, A takes this as a challenge. Dull-witted? Did he not just crack the tap code and discover X is up to something questionable, if not sinister? So A determines to moonlight as an amateur sleuth and discover X’s sins, perhaps even pitch an explosive exposé to his magazine afterward. He shaves his head and grows out his beard to somewhat disguise his appearance (his sister considers this an early midlife crisis), straps his son into his chest-mounted baby carrier (at two, the kid is nearing the weight limit cutoff), and starts hanging out at a park across the street from X’s office building. He wears dark sunglasses at all times to hide the direction of his gaze.

After a couple days of this, he notices X (also disguised but wearing that same unmistakable bright-red fitness tracker) leave his building and casually stroll toward the city boardwalk overlooking the inlet from which the city of Useless Bay takes it name, so-called because of its extreme shallowness at high tide and its vast stretches of wet sand at low tide. A and his boy follow at a reasonable distance, hoping, perhaps futilely, that the most celebrated detective in the Americas won’t notice he’s being followed. Children are noticeable, of course, but parents are generally not, he reasons.

This pattern continues: A discovers that X goes to the boardwalk once a week, though on a different day each week, always mid-day before the carnival rides open, always disguised, and collects a small package from a dead-drop customer suggestion box next to a disused cotton candy machine. Our narrator A watches sometimes from a distance, sometimes from the piers beneath the boardwalk, gazing up through the occasional knothole in the wood boards. He takes pictures on his phone when possible, though they tend to come out uselessly blurry, and dutifully records his observations, which form the first-person reports we are reading in the novel. After some weeks of this, one day he is standing out on the beach near the pier, showing his son a seashell while keeping one eye on X in the distance, when he notices a figure watching him through binoculars from the shadows under the boardwalk. The figure vanishes when he turns to it. Thus ends the first section of the novel.

The next section is narrated by B, who is, of course, the figure A noticed beneath the boardwalk. She is a gruff middle-aged PI who speaks in staccato bursts of odd phrases that sound almost like classic hardboiled clichés, but always slightly off-kilter; her opening lines are: “First report. Wednesday. Salted morning leaking through the city buildings, obscenely. Up to my you-know-whats in debt. Glad to finally have work. Took the bus to the calamari shop and pitterpattered it the rest of the way to the pier.”

B has been hired by the family of one of the victims of the Massacre (or at least B believes so at the time). The family has been alerted (possibly by X, possibly not) that a guy with a baby has been following X in order to discredit his case against the Filthy Five. The family is positive X found the correct murderer, and they want to make sure justice is served, as well as discover what malevolent forces hired A, whom they believe to be another investigator. So we follow B’s narrative for a while, seeing the actions of both A and X from a new perspective while getting a refreshing change of voice. We discover B is estranged from her longtime wife and has recently stopped drinking; she is now obsessed with Ramune soda, original flavor, the kind with the glass marble in the bottle-top. She despises A’s amateurish methods and obvious lack of professionalism as a detective, but she finds herself cracking an occasional smile at his antics with his son.

One day, she follows A who follows X to the usual dead drop, but they both notice X peek inside the package and then tap out an angry message on his wristband. From there, X travels quickly across the city (with A and B close behind), rapidly switching between rented bike, rented e-scooter, and hired car. A is barely able to keep up (his kid is delighted by the adventure), but B has no problem staying on A’s tail. They all come eventually to a run-down former prosthetics factory at the edge of town, where X angrily confronts a dark-coated barrel-chested man in a fisherman’s cap. Neither A nor B is close enough to hear what X is saying, but the two men are clearly arguing, possibly about money, given the size and shape of X’s regular packages. B begins to slightly doubt her client’s unwavering trust in X’s goodness; why is X receiving secret payments from this man? Probably just a regular case where the client wishes to remain anonymous—Lord knows B has had plenty of those herself in her day—but something about the whole setup strikes B as false. Just then, as she turns her head to consider for a moment, she notices someone behind her darting back around a corner. Thus ends B’s first section.

The pattern is now obvious to the reader, and the nested/matryoshka structure of the novel becomes clear. Another detective, C, is following B, and this next section is narrated by C, who turns out to be a former kid detective of the Nancy Drew type, now grown up and addicted to some unnamed drug originally favored by the seedy underbelly of Useless Bay, back when it had a seedy underbelly. In another radical change of voice, C speaks in a kind of strained super-positivity with underlying notes of bitterness, like a children’s book on acid. She favors exclamation points and double adjectives: “Wow, what a shitty factory! I thought to myself as I followed the grim brunette PI around the next corner.” We get an outsider’s perspective on B, who is much more talented and nimble than she led us to believe in her section. We follow C for a week or so as she follows B following A following X.

C has been hired by the girlfriend of one of the “gang” members accused of murdering the entire Investigative Unit, currently on trial and likely to be sentenced to life in state prison. The girlfriend is positive her boyfriend could never commit a single act of violence, much less be part of a series of coordinated murders. She claims that her boyfriend’s Tourette syndrome and his past convictions for minor crimes have led the media and X to paint him as an unstable psychopath, when really he just has a few mild verbal tics and used to be so poor that he needed to steal to eat. She heard from a friend that one of the victims’ families had hired B to ensure that her boyfriend and his comrades receive a guilty verdict, so she has decided to take matters into her own hands and hire C to investigate B and find the inevitable flaws in B’s investigation.

(Throughout these sections, the reader has begun to encounter occasional footnotes written in a strange voice from some unseen editor, intermingled through the narratives of A, B, and C. These notes elucidate background facts and sometimes even correct the reasoning of the other characters. It becomes apparent that this editor has compiled the book we are reading, though it’s as yet unclear how they got ahold of the reports from each investigator.)

Throughout C’s narrative, we find that her method of investigation differs markedly from both A’s obsession with facts and B’s methodical collection of hard evidence. Unlike the others, C has a style that doesn’t depend on asking direct questions or interrogating people, because she developed this style when she was a little kid whom adults wouldn’t listen to. She’s far better at tricking people into revealing information, slantwise.

Through C’s eyes, we see B discover that A is not a detective at all but merely a curious amateur. We also see A bring his toddler along with him less and less as the potential danger gradually dawns on him. X meets a few more times with the man in the fisherman’s cap, and they nearly come to blows over some disagreement, probably about money. At one point, a mugger attempts to rob C as she hides behind a dumpster watching B, but she easily overpowers him. She keeps his knife but gives him some money anyway, explaining that he can just ask next time instead of threatening her. He runs off, confused.

C’s section ends when she notices a hooded figure high in the rafters of an abandoned brewery, difficult to make out in the gloom but not really bothering to conceal itself. From its vantage point, the figure can see C, B, and A in their various hiding places as they watch X arguing with the man in the fisherman’s cap.

The figure, of course, is D, the final detective in the chain. But he is far stranger than the others. His narrative opens with a note explaining that it has been translated from an invented language or cryptolect called Detective’s Cant. D is some kind of mystical monk-detective, part of an underground proto-religion or cult that worships the twin gods of investigation and deductive reasoning. This cult esteems the genius gentleman detective X as a prophet or demigod, but D is gradually starting to harbor heretical thoughts and doubt his sect’s devotion to X. D’s abbot has assigned him to follow C for unknown reasons. (We later learn that the abbot is fearful about the others investigating the sainted X; the abbot wants to ensure no falsehoods are spread about his demigod.)

We see D move throughout the city like water, effortlessly taking on various disguises, becoming all but invisible when he pleases. He is offended by and dismissive of the amateurish methods of all the other detectives; D has been training in the dark deductive arts since he was a child. He takes rare snatches of sleep in a tiny cell concealed in the concrete underside of a bridge. He is the only member of his religion operating in Useless Bay; he only sees his fellow monks once per year at their annual gathering; the others live in similar cells hidden in other cities throughout the nation.

He tracks C through the city but soon develops detailed background reports on the other detectives in the chain as well. He is very thorough; through him we get a lot more personal information about the other narrators than we have seen thus far. Near the end of D’s first narrative, we discover that he is the unseen editor who has written the footnotes in the other sections. His own section ends as he observes C noticing B detecting A discovering that X has, in fact, been meeting with the president of the Fraternal Order of Displaced Policemen—he is the man in the fisherman’s cap, the former chief of police in Useless Bay.

From there, the novel winds backward through each narrator again, in the structure discussed earlier. C has another section where she both investigates B and attempts to discover D’s identity. B and A both follow suit, surveilling their respective mark while trying to shake their respective tail. In B’s second section, it becomes clear that X knows he is being followed by A. In A’s second section, A must sort through the various red herrings thrown off by X and figure out which, if any, are real clues. One particularly memorable scene involves all five detectives—X, A, B, C, and D—following each other in the tight confines of a city train, all elaborately attempting not to be noticed by the others but still maintain their surveillance. At another point, A meets with the mayor, ostensibly to fact-check an article he is working on but really to unearth some particular details of the Massacre that have never been made public; there is a digressive side plot where A and the mayor, who is a single parent herself, fall in love.

The structure moves backward to A and then forward again to D, at which point the four narrators finally become fully aware of each other and decide to meet up in secret and compare notes. They meet at a detective bar in a mossy alleyway—due to its lack of police, the city has an abundance of private eyes, and this is their watering hole. We catch brief glimpses of a wide variety of detective types at the bar: arson investigators, railroad detectives, insurance claims analysts, bounty hunters, skiptracers, investigative journalists, mystery novelists, corporate espionage experts, violent drunken Pinkertons, and even a masked vigilante in a dark overcoat loaded with expensive gadgets.

A, B, C, and a reluctant D have a long conversation and collectively deduce that X has framed the members of the Filthy Five, who are, in fact, not so filthy at all. The detectives piece together the vital hidden clue (which each of them had only collected a small fragment of individually) and realize the five alleged murderers could not possibly have committed the Massacre, as they were all out on a group camping trip to the Olympic Peninsula. It turns out that they weren’t housebreakers in Useless Bay, either. They did all serve prison time many years ago for burglary in the Seattle area, but their crimes were minor. The five of them met in an ex-convict support group and have been friends ever since.

The detectives also deduce that B’s client is not actually the family of one of the victims, as B first thought. Through an elaborate series of intermediaries, B was actually hired by X himself to keep an eye on A. X has therefore been aware this entire time of all the actions of A and B—but he is, perhaps, unaware of C and D. The four narrators band together, determined to bring X down and discover the real murderer. D takes this particularly hard, as he has spent the last several years worshiping X as a major prophet. He feels the stone pillars of his life and religion begin to crack. The others attempt to comfort him. They also instruct the amateurish A in the various arts of detection. He is gaining skill as an investigator.

In the last four sections of the novel—narrated by D, then C, then B, then A—our broken heroes work together to outwit the mighty genius of X, who seems three steps ahead of them at every point. They devise a plan for C and D to infiltrate the headquarters of the Fraternal Order of Displaced Policemen while A and B distract X. At the headquarters, a former Masonic lodge, C and D finally discover the truth: The Fraternal Order has itself orchestrated the events of the Massacre and the payments to X. (This is presented as a shocking twist, but most readers will have easily predicted it.) The former cops have been out of a job for four years since the abolition of their department, but rather than moving away and finding other jobs in other cities, they have spent the years organizing this elaborate series of murders to whip up public fear and get the police department reinstated. They hired X to frame the five accused, whom they hate as only a cop can hate an ex-con. (Why X agreed to this arrangement is kept secret until the epilogue.) The furious bull-necked cops of the Order discover the intruders and attempt to shoot C and D, who barely escape in a hail of gunfire with the crucial piece of evidence in hand.

In another twist, it turns out the mayor had a secret slush fund, out of which she’d been paying the members of the Order a sort of regular severance-salary to not cause trouble in Useless Bay. But one year ago, those payments were set to cease, hence the timing of the Massacre. Angry, A confronts the mayor about this, but she stands by her decision, saying it was the only way to keep the cops at bay and give the pilot program a fair chance. She and A argue but are soon reconciled; a footnote reveals they eventually move in together.

As the novel nears its end, a hemmed-in X launches a complex plan to assassinate A, B, C, D, and the mayor simultaneously. He nearly succeeds. We watch through A’s eyes (in the novel’s final section) as he deduces the existence of the five bombs, finally achieving the brilliant chain of reasoning and becoming a true detective as he’s always dreamed, outwitting even the magnificent deductive mind of X. He almost dies as he races alone in a speedboat out into the bay, the five bombs ticking down in the boat with him; he leaps into the water at the last second and swims as deep as he can, jolted through the dark currents as the bombs detonate massively just above the water, a safe distance from the city. He floats on his back a while in the cool night, stunned, half-dazed, gazing at the stars above him and reflecting on the infinite regress problem in detection (if p causes q, then what causes p?). He weeps when he thinks he nearly made his beloved son an orphan; he swims back to shore and collects the boy from his sister. The final section ends.

In an epilogue, D briefly explains how he compiled the threaded narratives, brazenly ignoring the orders of his abbot, the head of his order, who told him to keep all this a secret. Jaded, D renounces his faith and decides to publish the book as an exposé. He also reveals one final twist: X was not a private detective at all, but rather an undercover cop from Seattle working with the Fraternal Order of Displaced Policemen with the same goal of reinstating the Useless Bay Police Department; X was worried that the success of the pilot program would lead other cities to abolish or diminish their own police departments. X’s brother is the former police chief of Useless Bay, the man in the fisherman’s cap. This explains why A was originally unable to find any biographical information on X prior to four years ago: X doesn’t exist as a person. He is a creation of the Fraternal Order of Displaced Policemen and the undercover unit of the Seattle Police Department. His seemingly superhuman feats of reasoning were largely the result of a massive network of undercover cops working together, in constant communication (hence the wrist communication device that A mistook for a fitness tracker).

The scandal is made public, the members of the Fraternal Order are arrested by federal agents, and the cities of both Seattle and Useless Bay open a joint investigation into the undercover unit of Seattle PD.

On the final pages, D ruminates on the inadequacy of the US carceral system to deal with “crime” as a concept in general, and more specifically a crime whose architects sought to reinstate the carceral system in Useless Bay. It’s an endless circular chain: Punish the criminals using the same system those criminals sought to reinstate. Despondent, feverish, D therefore decides to perform one last desperate act before releasing his manuscript to the public: He breaks into the King County prison where so-called X and his brother are being held, awaiting trial. Disguising himself as a prison guard, D enters both their cells and quietly murders them in their sleep, using the same type of knife they used in the Massacre, reasoning that this is the only way to break the chain. He escapes undetected and flees to parts unknown on a night ferry, ocean glittering with starlight.

D’s final paragraph is an invitation to the other narrators to try and hunt him down, if they disagree with his reasoning. “I would welcome the chase, my friends, my fellow fools. I do not trust myself to judge myself, and I no longer trust any gods or demigods, but I trust you three. Godspeed.” He posts his manuscript online. The novel ends.